I rounded the corner of the games area, just looking for somewhere to sit. My right hip was bothering me and I wanted to do some quick stretches to open it up and relieve some tension.

The cafeteria offered many empty chairs but was also noisy and crowded, so as I wound myself through the full tables, brimming with customers, I was looking for a place of relative quiet. A place where I could take my ease, yet also watch people as they were coming and going.

And as I looked ahead of me, towards the reserved area where we were to have our party later, I saw my father.

He was looking right at me.

My dad hadn’t smiled much in recent years and he wasn’t smiling now. This unnerved me a little. To know that he might have been watching me this entire time, quietly assessing me as I wended my way towards him.

My father and I aren’t exactly close. This is not because there’s any animosity between us. It’s more because of who he is. Born in the 1930’s, he’s very much a man of his era – more of a silent provider and protector for his family, and not so much a friend.

I express surprise at seeing him there so early, and as I speak, he continues to watch me steadily with his calm blue eyes. His face is expressionless, so I have no idea what he’s thinking. But then he greets me readily enough and dives right into his recent health challenges.

“You are a rare bird,” his doctor told him at his last visit.

The description immediately captures my imagination. A rare bird.

My father is that.

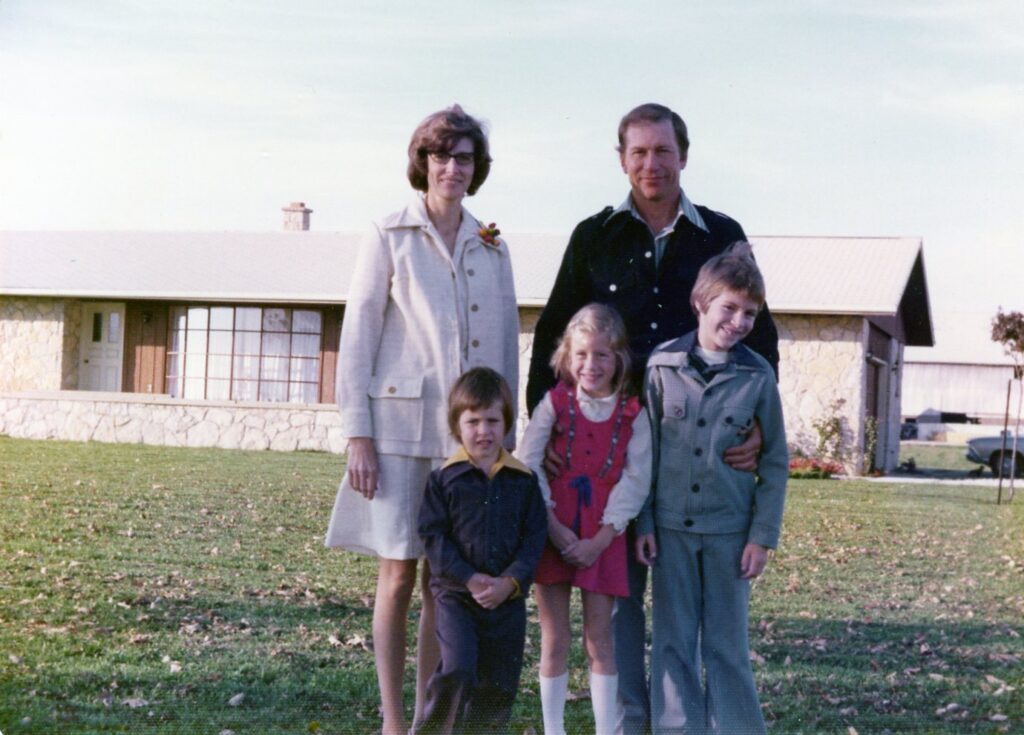

Described as “backward” by his mother when he was young, he’s a little socially awkward. A quiet and thoughtful type, he didn’t show any signs of marrying and settling down until he was almost thirty – late for the time. But my mother liked him. She was drawn by his courteousness, his intelligence, their shared love of choral music. He seemed like a bird in need of caring, so she took him under her wing and nurtured him.

She died a little over a year ago.

During the difficult last days and weeks of her life, my father had a silent heart attack. We only found that out months afterwards. Further diagnostic imaging has determined that the problem is due to amyloid plaques in his heart. The same plaques that tangle the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s syndrome are suddenly interfering with the activity of his heart. His doctors are trying to keep him alive.

I watch my father as he speaks, taking note of the dry patches of skin around his cheekbones, and the gauntness of his face. He’s alive at 90, but not exactly doing well. I guess that’s the best you can say of anyone who has had the good fortune to reach the age of 90.

In the past, I’ve often felt uncomfortable around my father. I find him too silent, too acquiescing, too passive. I’ve wanted more action from him. More vigour.

The funny thing is, I guess you could say the same thing of me. My discomfort around him likely stems from the discomfort of being myself. I am very much like him.

But there’s something about that phrase he used today – “a rare bird” – that softens me towards him. And then softens me towards myself. Maybe we truly are both ‘rare birds’. And if so, shouldn’t I appreciate all those things that make us different, rather than resent them? Shouldn’t I be proud of all the things that make us ‘rare’?

Neither of us are the life of the party. We’re both easily overlooked. We’re both a little too still, too passive.

But that quietness, that stillness, can also be a strength. Today, I notice how welcomed I feel within his attentive gaze. How reassured I feel by the thoughtfulness of his words. My father has never been someone who speaks in order to get attention. He speaks when he has something to say. And in a world where everyone is constantly talking over one another, all at the same time, this is refreshing. This is rare.

I once read an interview with the Canadian singer K. D. Lang. Praised for her unique voice, she was asked when she became aware of her talent. Incredibly, she said she doesn’t believe she’s unusual. In her opinion, everyone has a world-class talent. Maybe it’s not singing or dancing or acting, but each of us has something we do exceptionally well, better than anyone else on the planet.

At the time, I had scoffed at her words. I’ve never thought I had any particular skill or talent. But now, with that new sense of openness inspired by the phrase “a rare bird”, I give it some thought.

I know I like to listen. I like to hold space for people, and help them feel seen and heard. I like to reassure them that they’re essentially OK, that they can feel safe in my presence.

As I sit next to my father and we quietly discuss the events of the day, I find I am better able to appreciate the gift of a quiet presence. The gift of attentiveness. Of thoughtfulness.

And as I accept the quietness of my father, I find I am also able to accept the quietness of myself. I am finally able to accept us both as the rare birds we are.