The world is regenerating itself before our very eyes. Tender, green leaves are sprouting from branches, birds are singing, and cherry blossoms are showering us with their beauty.

A revitalizing force is springing up from the ground, spreading in all directions, and gaining energy.

Spring is the time when potential, possibility and transformation become more accessible. Not just to the trees, grasses and flowers, but to ourselves as well. We are part of this world, and the invigorating nature of spring affects us the same way.

Nevertheless, there are some people who more naturally exude the energy of spring during all seasons of the year. In Chinese medicine, these people are considered “Wood” people, and this nature corresponds most closely with the health of the liver.

Are you a Wood person? People who identify most strongly with the Wood element are like plants, and have a strong need for expansiveness and growth. They are motivated to plan and start big projects. They dare to create new things.

The key characteristics of a Wood person are the ability to plan, control and organize. A balanced wood type is creative, expressive, and highly motivated with an entrepreneurial temperament. The are not daunted by opposition, but actually thrive on it as they pursue their goals and ambitions.

This type of person may sound very invigorating and exciting. However, when a Wood person is excessive or stagnant, their personality can become difficult.

If their liver energy becomes blocked and excessive, a Wood type can become overly aggressive and dominating. They may want to be at the head of any project they are involved in and can become angry and frustrated when things don’t go their way. Liver/Wood people have a lot of excess energy built up, so when they become frustrated, they will raise their voices and shout.

On the other hand, if a Wood person is weak rather than a stagnated and congested, they will have a tendency towards depression rather than anger, as depression is anger turned inwards. Weak Wood types may be overly sensitive, with frequent dips into sadness and depression. They don’t have the energy to utilize their creativity and self-expression, so they will tend towards stagnation instead.

Having a regular creative outlet is important for everyone, but particularly for Wood people. Wood energy needs to find a way to spread outwards in order to prevent it from becoming stagnant. A creative outlet can be anything, from drawing, painting, model-building, writing, colouring, or journaling.

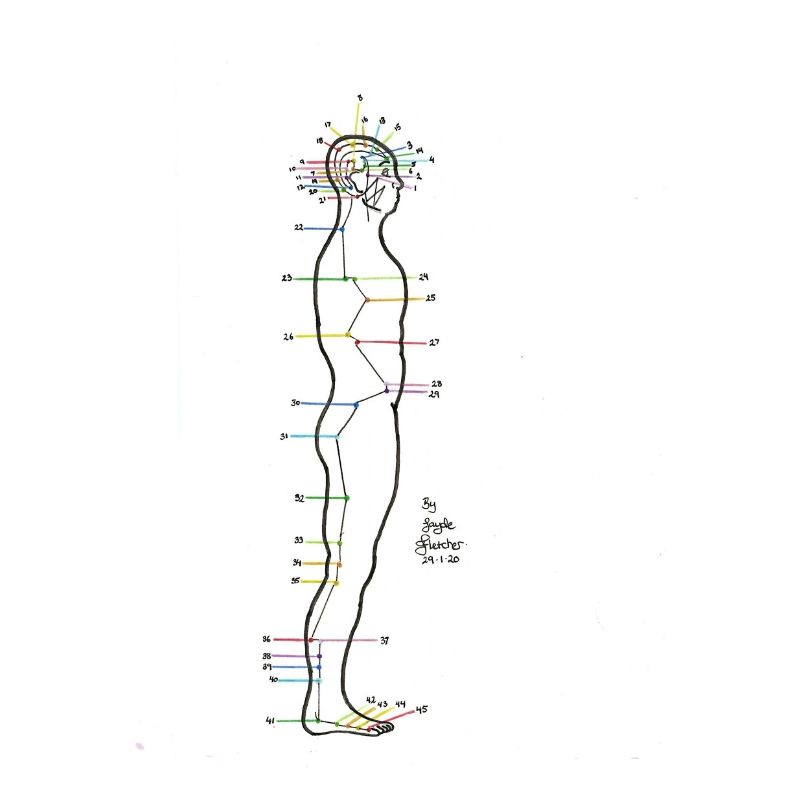

The organ of the liver a perfect match for the energy of spring, or of Wood. As a filtration organ, its energy is one of constant movement. It filters, detoxifies, metabolizes, nourishes, and stores blood. Good liver energy flows easily and expands outwards, just like Wood. It eliminates toxins from the body through flow of bile, and is also responsible for the removal of broken down red blood cells at the end of their life span, clearing space by removing toxic by-products from the system.

When liver energy is blocked, toxins are no longer be eliminated quickly and easily. Instead, they will tend to become stuck in the liver, or stored in various cells throughout the body, awaiting a time when the liver is no longer as bogged down with other activities that it can metabolize and excrete them properly. These stored toxins can eventually harden into cysts and tumours if kept around for too long. This is why cysts and tumours are common signs of blocked liver energy.

Common health complaints of the liver are all related to its ability to break down and remove wastes from the body. The accumulation of toxins can create inflammation, causing problems like hepatitis, and cirrhosis. If bile becomes stuck in its ducts and cannot flow well, gallstones will result. This congestion of bile will also prevent hormones from being broken down and removed from the body as efficiently, resulting in menstrual issues like painful menstruation, endometriosis, PCOS, PMS, and problems associated with menopause or infertility.

Because bile is responsible for both good digestion and elimination, a congested liver can cause abdominal bloating, gas, constipation, or IBS. A liver that fails to store sugars properly can contribute to diabetes or hypoglycemia. A liver that can no longer metabolize cholesterol as efficiently will lead to cardiovascular problems and chest tightness. Finally, a blocked liver can cause problems such as hypertension and depression.

The liver performs its housekeeping duties during the middle of the night, between the hours of 1 – 3 am. Therefore, frequent insomnia is another sign of liver dysfunction. Because the liver stores the blood which nourishes the nerves, muscles and ligaments, if the liver struggles there can be nervous twitching and spasms, or contracted muscles and tight ligaments.

Conventional medical treatment for most of these health problems typically involves the dispensation of medications, which is far from ideal. Pharmaceutical medications will themselves need to be broken down and metabolized by the liver, so they can only increase the stress placed on this vital organ.

If you know someone who is a Wood type, it is important that they ensure their liver is flowing well to keep their energy from becoming excessive and angry. Since the liver is a filtration and detoxification organ, a period of cleansing will usually set the liver right again. And spring, being the time of Wood energy, is the best time to do this.

In next week’s blog post, I will go over several different ways you can improve the health of your liver in a natural way, and keep it functioning optimally.